Yet, a law expert recently examined the case and deduced that a recent courtroom mistake from NASCAR might have turned the tide against itself.

Watch What’s Trending Now!

NASCAR’s counterclaim trap can backfire

On a recent episode of Bloomberg Law, NYU Law professor Harry First unpacked how a bold move by NASCAR has shot them back, handing 23XI and Front Row a critical edge just weeks before trial. First zeroed in on the counterclaim NASCAR filed, accusing the teams of price-fixing during charter talks.

“They (NASCAR) define a market, which was pretty much the same as the market that Michael Jordan defined… So they basically define the same markets,” First explained. “And the judge says, sorry, you’ve already admitted it… I mean, I think it’s pretty supportable on appeal, and there would have been ways to handle the complaint that didn’t fall into this trap, but they were sort of too clever by half.”

This admission sealed NASCAR‘s fate on market definition, with Judge Bell ruling the relevant space is strictly “premier stock car racing” with no room for IndyCar or F1 as substitutes. Back in 2024, charter negotiations between NASCAR and teams were not happening smoothly, and it got even more bitter when NASCAR arrogantly offered a “take it or leave it” offer, which eventually resulted in the October 2024 suit.

The counterclaim by NASCAR was meant to flip the script, but it proved that NASCAR is a 100% single buyer who dominates and has significant power over other sellers’ shares. In simple words, NASCAR itself agrees that it has a monopoly over the sport.

First noted the fallout, “It was a very clever counterclaim, but there was no requirement that they even needed to file it.” Now, with the monopoly power debate off the table, the matter shifts to anticompetitive acts like purchases and exclusive deals, which potentially maximize damages and pressure a pre-trial deal.

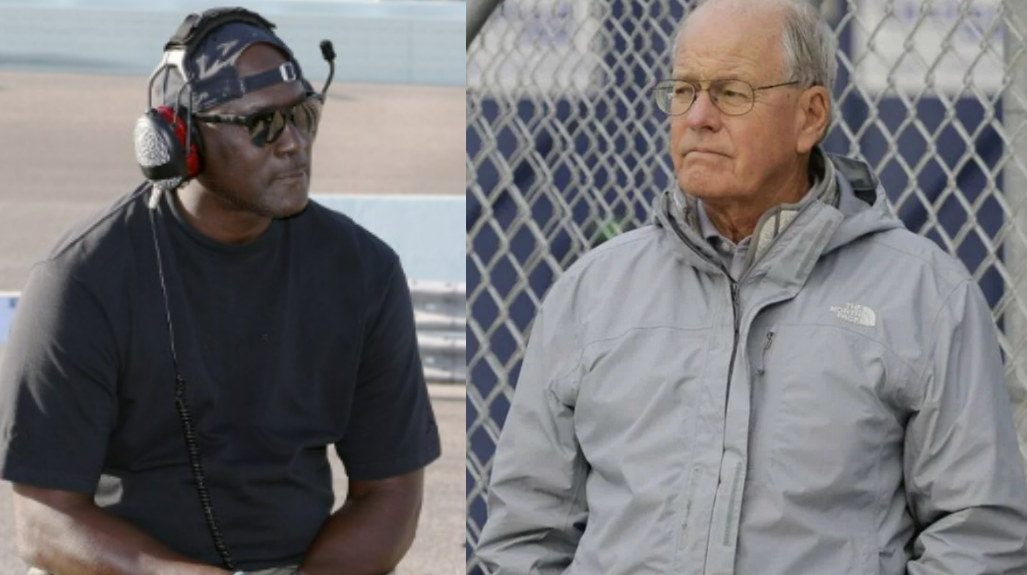

Michael Jordan doubled down in an August 2025 hearing, stating his stand as a supporter of the betterment of the sport. “Look, I’ve been a fan of the game for a long period of time. I’ve always said that I want to fight for the betterment of the sport… The point is that the sport itself needs to continually change for the better, for the fans as well as for the teams, as well as for NASCAR, too.”

These words echo Jordan’s entry into NASCAR in 2020, aiming to elevate the sport’s diversity and Black people’s representation in the sport. But now it’s a battle over revenue splits, where teams claim that the revenue they are getting now is not enough to maintain cars amid soaring costs.

First added on power dynamics, saying, “You have to have a monopoly power… as the sole buyer, and there have to be high barriers to entry… The judge found all of those things… It’s very hard to have a competing league.” A jury verdict could reshape charters, boost team payouts, or even invite appeals that drag into 2026, leaving the series in an unknown future.

As the trial date comes closer, these twists underscore the fragile balance between control and collaboration.

Teams trim suit to sharpen trial focus

As the trial date approaches, 23XI and Front Row dropped one of their claims (Section 1) so they can focus just on accusing NASCAR of monopolizing the sport. This clears the way for arguments about NASCAR’s market control.

The original lawsuit came from the 2024 charter talks, where 13 of 15 teams signed deals under pressure. It originally included complaints about NASCAR abusing its power and buying teams or tracks. Now, the case is simplified to focus mainly on NASCAR’s acquisitions, like the 2019 International Speedway purchase, which gave the France family more control over tracks and the sport.

Attorney Jeffrey Kessler acknowledged the shift, saying it keeps the jury laser-focused, “We are very pleased with the court’s decision today, ruling in our favor… This means that the trial can now be focused on whether NASCAR has maintained that power through anticompetitive acts and used that power to harm teams.”

This echoes the team’s running uncharted since July 2025, which was reversed post-appeals court, where drivers like Bubba Wallace and Tyler Reddick raced without the safety nets of revenue. Dropping Section 1 avoids legal debates over whether NASCAR has a monopoly and lets courtrooms save time and debate directly over how the monopoly power of NASCAR damages the sport from a fair split of revenues and charters.