Imago

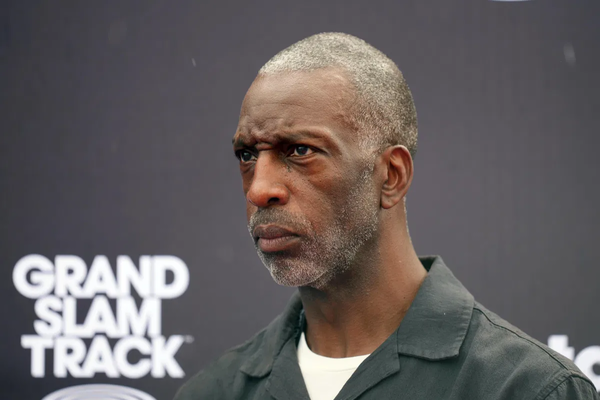

Noah Lyles, Michael Johnson, and Sha’Carri Richardson (Credits: IMAGO)

Imago

Noah Lyles, Michael Johnson, and Sha’Carri Richardson (Credits: IMAGO)

A professional track league promising millions in prize money, luxury athlete treatment, and a reimagined competition calendar — collapsed, in its very first season. The Grand Slam Track, founded by Olympic legend Michael Johnson, entered 2025 with claims of $30 million in investor commitments and ambitions to rival the Diamond League. Within months, it was drowning in debt, canceling meets, and owing athletes nearly $13 million in unpaid earnings. Behind the missed payments was a deeper structural problem, one that a veteran American coach says explains why some of the sport’s biggest stars, including Noah Lyles, never signed on.

Watch What’s Trending Now!

By midseason, Johnson admitted that lavish spending and a compressed four-meet schedule had strained the league’s limited reserves. Airfare for every athlete, single-occupancy hotel rooms, and extended acclimation periods were meant to elevate the track’s professional image. Instead, they depleted the budget before revenues could stabilize. A major investor’s withdrawal of an eight-figure pledge after the first meet in Kingston left the league unable to sustain the promised prize pools, which Johnson said were intended to exceed $3 million per meet. The gap between ambition and resources widened with each event, and the absence of several of the sport’s most marketable stars left the league struggling to deliver the marquee races it had envisioned.

Coach Rob shared a blunt assessment on his recent YouTube podcast of why certain elite athletes, including Olympic sprint champion Noah Lyles, may have stayed away. He said that even for athletes earning NIL deals, “those deals aren’t worth a lot of money… It is not life-changing money by any stretch of the imagination. Part-time job money at best.” In his view, the gap between the sport’s top tier and everyone else has created a pay structure that shuts out the biggest names. “The split comes where the top rung of athletes, the Noah Lyles, Sha’Carri Richardson, perhaps even a Gabby Thomas… they’ve priced themselves out of the market just being real because the way the system is set up.” Now, Sha’Carri Richardson, the reigning world 100m champion, is one of track and field’s most marketable stars and a frequent headliner at major meets. Moreover, her global popularity and high appearance demands often put her in the same exclusive pay bracket as Lyles. According to Rob, any attempt to set salaries based on realistic revenue from television rights and sponsorships would still leave the stars asking for more than a new league could sustain.

Coach Rob argued that while lower- and mid-tier athletes might accept modest payouts, the most recognizable figures command appearance fees that exceed what a start-up league can sustain. Under the current structure, some stars can earn more simply for showing up to a Diamond League meet than from winning its prize purse. This dynamic extends to the sport’s biggest names, including Noah Lyles and Sha’Carri Richardson, both of whom remain among the most marketable faces in track and field yet have shown little public interest in a new $30 million project backed by Michael Johnson. “Some of the athletes are now priced out of the market because those at the bottom, they’re happy to get anything. Those in the middle will accept the peanuts or even something better than peanuts to be real. But then the ones at the top, they say, ‘I’m better than this.’” Without their buy-in, he warned, no league could expect to draw consistent public interest, especially in the United States.

Imago

Credits: IMAGO

His perspective framed the challenge in long-term terms: convincing the sport’s biggest names to commit to building a product whose full success might not arrive until after their careers had ended. The WNBA, he noted, grew in stature only after its early stars accepted salaries well below their market worth. He stated, “In the WNBA, we had women who played for less than $100,000 for a very long time. They might have been MVPs and the best ones in the league, but they had to play for that amount and be committed to playing for less than that because that’s just what the league was going to pay them… salaries are climbing now for a whole bunch of different reasons, but it still gives you a framework of can you get the best athletes in the world to agree to help build something when it’s not in its full effect. Grand Slam Track set out to accomplish something very grand.”

Grand Slam Track’s vision, he said, was closer than any previous attempt to modernize the sport, but without cooperation across the athlete spectrum, it risked becoming another ambitious experiment that could not survive its first season. As Coach Rob further added, “Using that as an example, Noah LS was the hot thing coming off of the Olympics and the World Championships in 2023. His profile is very different than everybody else. He is an example of an athlete who got priced out of the market. And I’m going to land the plane here. When you look at how leagues form and how they survive, you’re going to need athletes to buy into a situation that’s bigger than them.” And as it appears, Noah Lyles saw the financial storm coming for Grand Slam Track, and he said so plainly.

Noah Lyles’ warnings on Grand Slam Track’s finances prove uncomfortably accurate.

Noah Lyles did not arrive at his misgivings about Grand Slam Track by accident. Long before the league’s early shutdown, he had questioned whether its ambitions could withstand the realities of sponsorship scarcity and limited commercial reach. “Money is not the thing that’s going to drive me every time… who are your outside sponsors, who are your non-track and field sponsors… I haven’t even heard a block’s sponsor,” he remarked in March, when GST was still staging events. While careful to say he wished for its success, his reservations focused squarely on whether it could attract the level of financial and promotional backing required to keep elite athletes committed.

Imago

ATHLETISME: Meeting Herculis – Diamond League – 11/07/2025 – Monaco Noah Lyles MonacoMonaco PUBLICATIONxNOTxINxFRAxBEL Copyright: xWilliamxCannarellax

When the Los Angeles finale was cancelled three months later, the development confirmed for Lyles what he had feared. Speaking with James Emeritt in June, he described the outcome without satisfaction. “I’d say my predictions were kind of dead on, unfortunately… that means that you weren’t able to make it the first full year, full season, accomplishing all the goals that you had planned.” His tone conveyed neither triumph nor vindication, but rather a recognition that the financial fragility he had identified early on had proved decisive.

For Lyles, the implications reach beyond one league’s dissolution. “That’s very saddening because that doesn’t just affect this league Grand Slam, but it affects every other athlete that you know might have leagues in their head in the future,” he said. The absence of sustained sponsorship and audience engagement, in his view, not only curtailed GST’s ambitions but also cast doubt on the viability of similar ventures. His comments underscored a consistent position: professional track and field can only be sustained when it secures both commercial relevance and genuine value for its competitors.