Imago

Credits: TKO Holdings

Imago

Credits: TKO Holdings

It’s a time of massive change in boxing. Perhaps the signs were already there. During a media appearance, the head of TKO Holdings, Ari Emanuel, suggestively quipped, “Who knows what’s going to happen with the Ali Act?” For a sport that captivates audiences within the confines of the ring, the next major fight may be taking shape far beyond the ropes. As days pass, clear lines are being drawn around the proposed ‘Muhammad Ali American Boxing Revival Act.’ It was on July 23 when Representatives Brian Jack and Sharice Davids introduced the bipartisan bill in the U.S. Congress. Since then, a quiet legislative move has rippled into a fierce debate.

Watch What’s Trending Now!

To put it in perspective, the proposed legislation, informally referred to as the ‘Ali Revival Act,‘ aims to ‘amend the Professional Boxing Safety Act of 1996 to establish requirements for unified boxing organizations, to further enhance the well-being of professional boxers, and for other purposes.‘ However, those very intentions have sparked a polarizing discussion. If enacted, critics argue, the Revival Act could contradict the foundational principles of the original Muhammad Ali Act, particularly its aim to protect fighters from exploitative business practices. They worry. The new framework may disproportionately benefit a single company at the expense of fighters and independent promoters. How so? Before we get into that, let’s understand…

ADVERTISEMENT

Why is there a need for the new bill?

A few months ago, Zuffa Boxing re-emerged in the boxing scene through a high-profile partnership between TKO Group Holdings, Sela, and His Excellency Turki Alalshikh’s Riyadh Season. The promotion, formalized in June 2025, is led by Dana White, the longtime president and now CEO of the UFC. Though welcomed, the move sparked notable concern in several circles. Early indications suggest that Zuffa Boxing may adopt a structure similar to that of the UFC. A centralized model in which one entity oversees matchmaking, rankings, and championships.

Imago

UFC CEO DANA WHITE with post event media during the UFC 304 event at Co-op Etihad Campus, SportCity, Manchester, England on the 27 July 2024. Copyright: xAndyxRowlandx PMI-6350-0002

So critics worry that the Muhammad Ali Revival Act is not merely about improving safety and regulation. It’s rather an attempt by TKO to legally consolidate control in boxing in a way that mirrors its approach to mixed martial arts. Such a model could sidestep existing protections in the original Ali Act of 1999 and its precursor, the Professional Boxing Safety Act of 1996. More significantly, it will shift the power dynamic further away from fighters and independent promoters.

ADVERTISEMENT

Before diving into the finer details, a few clarifications are important.

Top Stories

Floyd Mayweather Faces Threat of Losing Post-Boxing Empire as 8-Figure Debts Mount: Report

“Rest in Peace”: Condolences Pour In as Legendary Coach Freddie Roach Mourns Personal Loss

Anthony Joshua Discharged From Hospital as Police Arrest Driver Over Fatal Car Crash in Nigeria

Where Is Reina Tellez From? Nationality, Ethnicity, and Religion of Amanda Serrano’s Opponent

Floyd Mayweather Breaks Silence as $402M Real Estate Deal Goes Allegedly Wrong

ADVERTISEMENT

Tracking the Ali Revival Bill: Where things stand

First, the Muhammad Ali American Boxing Revival Act is currently a ‘proposed’ piece of legislation. It has yet to become a law. The first step in the legislative process involves referral to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce. It’s the same committee that reviewed both the 1996 Professional Boxing Safety Act and the 1999 Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act.

Once the committee chooses to advance the bill after debate and possible amendments, the full House of Representatives will vote on it. If passed by a simple majority, it moves to the Senate, where it may be approved as-is, amended, or rejected. If both chambers agree on the final version, the bill proceeds to the President’s desk to be signed into law.

Second, and equally important, the Revival Act intends to amend the original 1996 Act. Not the 1999 Reform Act.

ADVERTISEMENT

What the Ali revival act proposes and what it could change

On the surface, the Revival Act presents itself as an egalitarian effort. It is designed to improve conditions for professional boxers and strengthen procedural safeguards within combat sports. The stated purposes of the Act are as follows:

- To provide increased choice and opportunity to professional boxers by allowing a professional boxer to choose to participate in the alternative system offered by a unified boxing organization, and

- to further enhance safety precautions that protect the well-being of professional boxers

ADVERTISEMENT

To that end, several proposed measures have drawn interest and even approval from parts of the boxing community:

- A national minimum payment of $150 per round

- A national minimum health coverage amounting to $25,000

- Mandatory medical testing, including MRIs, EKGs, pregnancy tests, and drug testing

Additionally, contracts reportedly offered to fighters may promise structured fight schedules.

ADVERTISEMENT

To set the context: reportedly, only six U.S. states mandate a minimum per-round payment. In each case, the figure falls below the proposed $150. The vast majority of states don’t seem to have such a requirement. Similarly, the proposed $25,000 in health coverage appears to exceed what is currently provided in 43 states, making it a potentially significant upgrade in fighter protections.

Yet, for all the health-and-safety talk, the most significant and debated aspect of the Revival Act remains the introduction of Unified Boxing Organizations (UBOs). It’s a concept that could reshape how boxing promotions operate, regulate, and reward fighters.

ADVERTISEMENT

UBOs explained: What they are and what the Act proposes

The Act clearly states: “The Professional Boxing Safety Act of 1996 (15 U.S.C. 6301 et seq.) is amended by adding at the end the following: ‘‘SEC. 24. UNIFIED BOXING ORGANIZATIONS. (a) ALTERNATIVE SYSTEM FOR COMPLIANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF THIS ACT—A unified boxing organization (in this section referred to as a ‘UBO’) shall be deemed to be in compliance with the requirements of this Act if the UBO meets the conditions of this section with respect to— ‘(1) each boxer under contract with the UBO;’ and ‘'(2) each professional boxing match organized by the UBO (in this section referred to as a ‘covered match’).’”

So, based on the provisions outlined above, Zuffa Boxing could very well become the first recognized UBO. But that’s exactly where the major concern arises.

ADVERTISEMENT

Understanding the implications of a Unified Boxing Organization

As an ‘alternative system for compliance,’ the Act appears to open the door for a UFC-style boxing structure. Without the traditional requirements, like independent rankings, third-party sanctioning bodies, or the transparency standards set by the original Muhammad Ali Act, a Unified Boxing Organization (UBO), such as Zuffa, could adopt a self-contained regulatory model and still be deemed legally compliant.

Critics view the clause as a legal workaround to the protections accorded by Ali Act. By meeting a newly defined checklist that includes provisions for health, safety, and fighter pay, a UBO would manage its own belts, rankings, and matchmaking. Thus, it could effectively sidestep the checks and balances that the original Act was designed to enforce.

In theory, the UBO concept need not be controversial. Fighters should have the freedom to align with the promotion of their choice, based on what best suits their careers and protections.

UBO: A game-changer or power grab?

But a closer look suggests the UBO provision could undermine the foundational protections established by the Professional Boxing Safety Act of 1996. That Act was created, in part, to shield fighters from exploitation, especially by powerful promoters who also acted as managers. The situation often resulted in serious conflicts of interest. Due to the absence of strong federal oversight, these dual roles often led to fighters being dragged into long-term, one-sided contracts with limited legal recourse.

The original Act strived to prevent any single entity from gaining excessive control over a boxer’s career, particularly over finances, rankings, and matchmaking. With the introduction of a UBO, however, a single organization could once again gain centralized control over all key aspects of a fighter’s professional trajectory, even their earnings, title opportunities, and career advancement.

Likewise, the proposed minimum payment under the Revival Act has drawn scrutiny. $150 per round may sound like progress. But a closer look raises concerns. For context, depending on their record, visibility, and promotional backing, boxers fighting on undercards, even at non-televised local events, typically earn between $1,000 and $4,000 for a four-round bout.

Under the Revival Act’s proposed standard, a four-round fight would guarantee a minimum of $600. Deductions for trainers, cut men, managers, and other expenses subsequently follow. That number, critics argue, could end up being less than current averages in many jurisdictions. It may even normalize lower payouts under the guise of standardization.

Not long ago, the UFC and Dana White agreed to a $380 million settlement in a class-action lawsuit brought by fighters who competed from 2010 to 2017. The fighters alleged wage suppression and anticompetitive behavior. These are issues some worry could resurface in boxing under a similarly centralized model.

Arguments in favor of the Muhammad Ali Revival Act

Yet, the TKO and Dana White-backed Muhammad Ali Revival Act has garnered noteworthy endorsements from influential figures and institutions. Among them are the Association of Boxing Commissions (ABC) and Lonnie Ali, widow of Muhammad Ali. “If Muhammad were with us today, he would want to ensure the sport of boxing in America remained strong and viable for generations to come, providing opportunities for other athletes to pursue their goals and dreams, just like he did. Given its enhanced protections for boxers, I believe Muhammad would be proud to have his name associated with this bill,” she has conveyed.

Legendary trainer Teddy Atlas, a vocal admirer of Dana White, also shared his endorsement: “I want to see him enhance it (the existing act). I want to see him take it to a better place. I want to see the fighters better protected. I want to see more transparency in the sport, in promotional areas, and in different areas. I love Dana White. I love what he’s done with the UFC.”

However, these endorsements coexist with growing skepticism. Critics argue. Rather than refining the existing regulatory framework, even if flawed, the push for an entirely new amendment may be a strategic move. It could potentially consolidate control and circumvent critical safeguards already in place.

Questions and concerns around the Revival Act

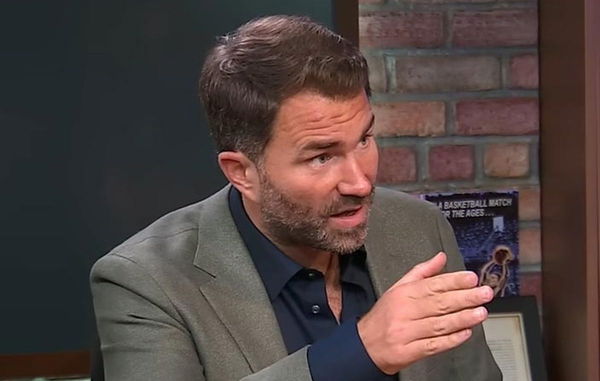

Eddie Hearn, head of Matchroom Boxing, despite a close relationship with Dana White, didn’t mince words in his criticism of the Revival Act. The English promoter, who holds significant influence in the U.S. boxing scene, framed the bill bluntly: it’s about ‘ownership and control.’ Somewhat unexpectedly for a promoter, Hearn was unequivocal in his stance. Rather than consolidating more power among promoters, he argued, the priority should be safeguarding fighters’ rights.

Privy to the concerns of many athletes, Eddie Hearn shared that several fighters had approached him with unease. “The fighters that I’ve spoken to have certainly raised a lot of eyebrows, saying, ‘Why are you trying to abolish an act that is there to protect us?’” he noted.

Combat sports attorney Erik Magraken also expressed concern over the proposed amendments, particularly their potential impact on fighter protections. Responding to a series of queries, Magraken echoed the skepticism shared by others, focusing his critique on the UBO, what he described as a ‘super promoter.’ “This new breed of promoter doesn’t have to comply with the Ali Act,” he stated.

Over time, such practices tend to centralize power. The UFC under White stands as a prime example. Despite the existence of other MMA promotions, the UFC, with its own titles and rankings, has become the dominant force in the sport, shaping both its commercial narrative and competitive structure.

The greatest anxiety, however, may lie with small-time promoters who now face a potential existential crisis under the UBO framework. Major promoters with deep pockets might have the resources to adapt and compete. But those organizing local or state-level events, often showcasing regional talent, could be pushed out of the ecosystem entirely since they won’t be able to pay the minimum pay required and provide the mandatory insurance coverage for fighters.

The proposed requirements could significantly raise operational costs. For small promoters, this could make organizing events more difficult. It could also hinder their ability to attract and retain promising talent. If enacted, these changes may unintentionally clear the field for someone like TKO to sign up young, underserved fighters. They would gradually consolidate influence over boxing’s next generation.

In trademark fashion, Oscar De La Hoya, a longtime Dana White critic, didn’t hold back in his criticism. “As TKO prepares to enter the boxing space, the first thing they want to do is change [the Ali] Act and leave fighters vulnerable. TKO needs this to change so they can implement the exact same unethical business tactics in boxing that they used to create a monopoly with the UFC.”

Clearing the air on the Muhammad Ali Revival Act

Representative Brian Jack, who introduced the bill, earlier told Sports Illustrated that ‘the Ali Act would be unchanged.‘ According to him, the intent is to clarify some of the ambiguities that have plagued the original law. Importantly, the bill does not seek to dismantle the existing boxing structure. Instead, it proposes a parallel, voluntary pathway through the UBO system. It gives fighters the freedom to pursue rankings and titles within this new framework.

“The thrust here is we have a system, and if you want to stay in that system, you can. We are not touching the Ali Act. Instead, we are adding an additional section to the U.S. code that allows for the creation of UBOs, and we’re touching the PBSA [Professional Boxing Safety Act] by amending it. I kind of describe it like on a whiteboard you’ve got a big circle with the sanctioning organization model. Then you’ve got a UBO model. That’s another circle. And the only overlap, so to speak, is that of amending for minimum fighter pay and specified health coverage. That applies to both models,” the Republican Congressman from Georgia said.

But is that really how things stand?

If one reads between the lines, a different picture begins to form. The UBO would technically exist alongside the current system. But it may likely draw fighters, resources, and viewership away from the traditional sanctioning bodies. There will be centralized power under TKO, a for-profit company with full control over rankings, belts, and matchmaking.

The idea of ‘choice’ may be misleading. Many perceive the traditional system as slower, riskier, or more fragmented. So in practice, newer fighters could feel compelled to sign with the UBO. What if they offer more lucrative opportunities early in their careers?

In essence, the bill may not abolish the current model outright. Instead, it may establish a parallel system not bound by the same neutrality and checks. The crucial separation between promoter interests and fighter rankings may cease to exist.

Final thoughts

Perhaps Austin Trout summed it up best. Many of today’s concerns might never have arisen had the original Muhammad Ali Act been properly enforced.

Seemingly, the Ali Act has been ineffective because the ABC doesn’t enforce it. Sanctioning bodies continue to manipulate rankings, and promoters maintain an outsized influence over belts and matchmaking. “If no one’s going to uphold the rules, what is the point of the rules? That’s boxing in a nutshell,” Trout said.

For now, the boxing world can only wait. The Muhammad Ali Revival Act will move through the slow, bureaucratic stages of review and approval. Perhaps in the meantime, further clarifications will emerge. Ones that might quell the mounting doubts and provide clearer direction for the sport’s future.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT